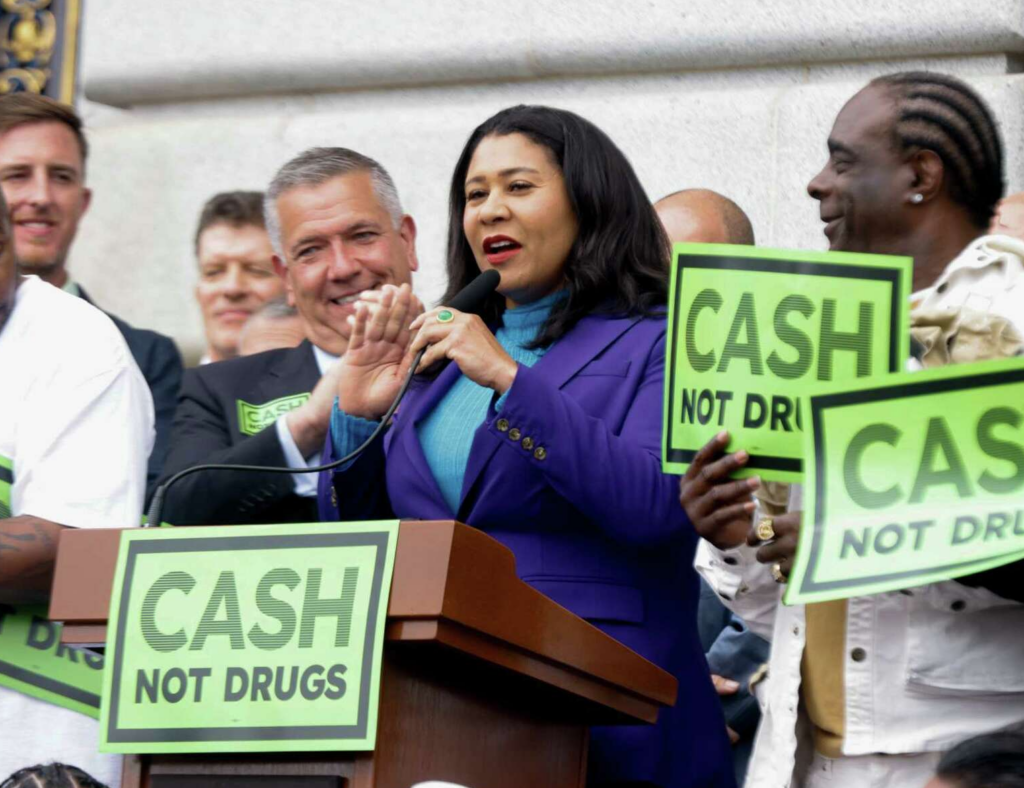

San Francisco has recently proposed a groundbreaking “Cash Not Drugs” legislation aimed at combating the city’s drug crisis by offering $100 per week to individuals who test clean from illicit drugs. This innovative approach, rooted in the principles of contingency management, has sparked considerable debate. But do recovery incentives like these actually work? Let’s delve into the research and cost-saving implications of such programs.

The Concept of Recovery Incentives

Recovery incentives, particularly in the form of contingency management (CM) programs, have been a subject of study for several decades. CM programs reward individuals for positive behaviors, such as maintaining sobriety, attending therapy sessions, or achieving treatment goals. These rewards can range from vouchers and prizes to, in the case of San Francisco’s proposal, direct cash payments.

California is the first state to receive federal funding to offer recovery incentives as a benefit to Medi-Cal beneficiaries. Roots Through Recovery has been participating in DHCS and UCLA’s pilot CM program, offering small financial incentives to patients with Stimulant Use Disorder for drug tests negative from stimulants.

Efficacy of Contingency Management Programs

Research has consistently shown that contingency management is one of the most effective strategies for treating substance use disorders. A comprehensive review published in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment found that CM significantly improves treatment retention and drug abstinence rates compared to standard care. Participants in CM programs are more likely to stay engaged in treatment and achieve longer periods of sobriety.

A study by Petry et al. (2005) demonstrated that participants receiving monetary incentives for negative drug tests had higher rates of continuous abstinence compared to those who did not receive such incentives. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Prendergast et al. (2006) highlighted that CM programs yielded a moderate to large effect on reducing drug use during and after the intervention period.

Cost-Saving Basis for Recovery Incentives

Implementing recovery incentives may initially seem like an additional financial burden, but the long-term cost savings are substantial. Substance use disorders impose significant economic costs on society, including healthcare expenses, criminal justice costs, and lost productivity.

A report by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) estimated that every dollar invested in addiction treatment programs yields a return of between $4 and $7 in reduced drug-related crime, criminal justice costs, and theft. When healthcare savings are included, total savings can exceed costs by a ratio of 12 to 1.

The Case for San Francisco’s “Cash Not Drugs” Program

San Francisco’s proposal leverages these findings by offering a tangible, immediate incentive for individuals to abstain from drug use. The $100 weekly reward could provide the necessary motivation for individuals struggling with addiction to commit to their recovery journey. This program could also alleviate some of the economic pressures that often drive individuals back to substance use, such as financial instability and lack of access to basic needs.

Moreover, by reducing drug use and promoting recovery, the “Cash Not Drugs” program could lower the overall demand on the city’s healthcare and criminal justice systems. Fewer emergency room visits, reduced incidences of drug-related crimes, and decreased need for law enforcement interventions are just a few of the potential benefits.

Addressing Criticisms

Critics of monetary incentives for recovery argue that such programs might foster dependency on financial rewards or be perceived as rewarding individuals for not engaging in illegal activities. However, proponents contend that the ultimate goal is to support individuals in achieving long-term sobriety and reintegration into society. The immediate benefits of reduced drug use and improved quality of life far outweigh these concerns.

Many Bay Area residents took to social media to voice concerns, and question where the money for this program will come from, citing San Francisco’s schools and infrastructure that need attention. Without citing research and sharing the potential cost savings of a program of this nature, it’s no surprise that this announcement was met with skepticism and concern.

Conclusion

San Francisco’s “Cash Not Drugs” legislation represents a bold and innovative approach to tackling the city’s drug crisis. By building on the proven success of contingency management programs, the initiative offers a practical, evidence-based solution to support individuals in their recovery journey. With the potential to yield significant long-term cost savings and improve public health outcomes, this program could serve as a model for other cities grappling with similar challenges.

As the city embarks on this new path, it is essential to monitor the program’s outcomes closely and remain open to adjustments based on empirical evidence and participant feedback. Ultimately, the success of the “Cash Not Drugs” program could pave the way for a broader acceptance and implementation of recovery incentives nationwide.

Resources

Petry, N. M., et al. (2005). “A randomized trial of reinforcement-based treatment for cocaine dependence.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(2), 277-285.

Prendergast, M., et al. (2006). “Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: A meta-analysis.” Addiction, 101(11), 1546-1560.

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). “Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition).”

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). “Is drug addiction treatment worth its cost?”

4 thoughts on “Cash Not Drugs: Do Recovery Incentives Work?”

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. I appreciate the honesty and authenticity you bring to every post. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

Pingback: San Francisco proposal incentivizes sobriety by giving drug users weekly cash benefits - Hecho en California con Marcos Gutierrez

You are a very bright individual!

Interesting take on using cash in recovery—thought-provoking approach!