Most people who work in recovery or are in recovery themselves, or both, would agree that social connections are important for long-term recovery from addiction. The level of external support individuals have is often referred to as Social Capital or Recovery Capital, which for the purpose of this article, we are defining as:

The abundance of positive social relationships and connections, specifically across the domains of social supports, spirituality, life meaning, and involvement in a recovery community.

Individuals coping with substance use or dependence are often treated as patients with an acute illness, as one would be treated in the ER or urgent care:

- Assessment;

- Intake;

- Treatment; and

- Discharge;

which research proves is not an effective approach to achieving sustainable recovery. Alexandre Laudet, PhD., Director of the Center for the Study of Addictions and Recovery (C-STAR) at the National Development and Research Institutes suggests that if one considers addiction to be a chronic condition, a conjecture increasingly accepted in the field, then being in remission (recovery) should be thought about in terms of a long-term process that unfolds over time, rather than a time-limited ‘event’.

The theory of recovery capital suggests that the more abundant our recovery capital, the greater the likelihood we will remain in recovery. We see the value of this connection to community at the very core of sober living environments and groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, an international fellowship of more than 2 million men and women with an alcohol dependence, and their associated groups including Narcotics Anonymous and Cocaine Anonymous. Not surprisingly, we see poorer outcomes and frequent relapse in those who leave treatment, even long-term treatment, without a social network to support them in recovery.

Longitudinal studies, like that of Dr. Laudet’s, exemplify the critical value of social and recovery capital at the various stages of recovery, allowing us to most effectively incorporate these practices into assessment, treatment planning and discharge planning. Whether you’re a staunch supporter of 12-step recovery, a believer in the value of psychotherapy or biomedical treatments, or have embraced the combination of these approaches, it is becoming increasingly more difficult to deny the impact of connections and social support in long-term recovery, both positive and negative.

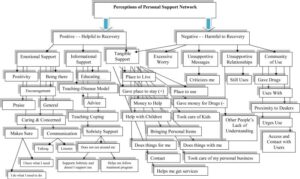

Taking into consideration the number of connections isn’t enough to determine the impact they will have on an individual in recovery; rather, we must account for the value of each connection, or perceived value. The complex web below shows that our social and peer connections differ in impact based largely on perception. For example, communication can be seen as a sign of caring and concern–a component of emotional support–and therefore, helpful to recovery. In contrast, criticism (a form of communication) may be perceived as unsupportive and therefore harmful to recovery, regardless of intention.

What if having a large, closely-knit social and peer network was detrimental to recovery? The role of social networks and peer support in recovery has been studied for quite some time; and although the research overwhelmingly sways in the direction of the positive impact social networks play in our recovery, a recent NPR article about the increase in opioid abuse in rural communities–in sharp contrast–points to social networks as a main contributor.

The story follows Melissa Morris, whose story of addiction started like many others–with a prescription to Percocet, an opioid pain killer. She got hooked, and when the Percocet stopped getting her high, Morris then started injecting Oxycontin. After that, she got her hands on Fentanyl patches, a highly addictive and potent opioid, and would chew on them instead of applying them to skin as the package directed. When the prescriptions stopped coming, she turned to a cheap and easy option: heroin. Morris’ story is much like what we are seeing across the country, and especially in rural communities.

The facts:

- The CDC reports three out of four new heroin users report abusing prescription opioids prior to trying heroin.

- In the U.S., heroin-related deaths more than tripled between 2010 and 2015, with 12,989 heroin deaths in 2015.

- According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioids were involved in more than 33,000 deaths in 2015 — four times as many opioid-involved deaths as in 2000.

- A recent University of Michigan study found the rates of babies born with symptoms of withdrawal from opioids rising much faster in rural areas than urban ones.

So what role do social networks play in the opioid epidemic? The publication about rural Colorado, titled “Rural Colorado’s Opioid Connections Might Hold Clues To Better Treatment”, in addition to limited access to alternative treatments for pain like physical therapy, found in speaking with individuals struggling with opioid addiction that these communities saw an increase in misuse and dependence because rural residents know and interact with roughly double the number of people an average urban resident does. Counterintuitively maybe, this “small town” social network provides members of rural communities twice the number of opportunities to access drugs, according to Kirk Dombrowski, a sociologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

“So some of those social factors of being in a small town can definitely contribute,” Dombrowski says.

Melissa Morris of Sterling, Colorado. Credit: Luke Runyon/Harvest Public Media

But, like Dr. Laudet’s findings, the Colorado resident Melissa Morris describes how the size of your social network doesn’t define the risk, but rather, the value of the network is often at play. She says that close social ties in her town may have contributed to the spread of opioids there as those bonds can spread drug use quickly, however they can reduce the spread of drugs in other ways. Morris, who is now on Suboxone to help her with her opioid addiction, recently recruited two opioid-dependent friends to the clinic she goes to weekly for treatment.

“I used to sell them pill and heroin,” says Morris, who is now helping these friends get clean. “And so I do have hope. I’ve seen those success stories.”

This consideration of the value, and perceived value, of social networks has great implications for the field of addiction research and treatment. Often times, providers ensure clients broaden their social network and surround themselves with “positive influences”, but as treatment providers, it should be a regular practice to give individuals in recovery the tools needed to regularly take an inventory. We should assess the impact individuals have (are they helpful or harmful?) often as this can frequently change, as our once drug dealers can enter treatment and have a positive impact on our recovery.

Roots Through Recovery offers drug rehab in Long Beach as well as sober living options. Visit 3939 Atlantic Ave, Suite 102 Long Beach, CA 90807 or call (866) 766-8776 for immediate assistance.