I think all along we should have been singing love songs to them, because the opposite of addiction is not sobriety. The opposite of addiction is connection. –Johann Hari

In Johann Hari’s landmark TED Talk in June 2015, titled “Everything you think you know about addiction is wrong”, he explains the psychology behind addiction and how the criminalization of and stigma of the addicted person actually produce the opposite of the intended outcome. Saying “drugs are bad” and that they are addictive does nothing to address the issue of why people begin using drugs in the first place, such as to self-medicate or numb the unpleasant feelings brought on by past trauma, as we wrote about in an earlier blog. Hari says, essentially and quite simply, everything we’ve been doing to get people to stop using drugs has been wrong! And by the way, he didn’t arrive at this conclusion by chance or do it on his own; in fact, he had quite a bit of help from friends, scientists and the country of Portugal.

Hari first began to delve into this topic the way many of us have: because our lives have been touched by addiction, either we have experienced an addiction ourselves or someone close to us has. The fascinating thing about addiction is that the common societal attitude toward addiction is largely based on decades old research that has since been debunked, and yet, we continue to think that these two things are the key: 1. Drugs are addictive, and 2. People will stop using drugs if we punish them. The research, including that of Dr. Alexander referenced by Hari, shows that these two points are inherently wrong. Dr. Alexander’s famous “Rat Park” study tells us something different about addiction. Here is an excerpt from Hari’s TED Talk:

You get a rat and you put it in a cage, and you give it two water bottles: One is just water, and the other is water laced with either heroin or cocaine. If you do that, the rat will almost always prefer the drug water and almost always kill itself quite quickly. So there you go, right? That’s how we think it works.

In the ’70s, Professor Alexander comes along and he looks at this experiment and he noticed something. He said ah, we’re putting the rat in an empty cage. It’s got nothing to do except use these drugs. Let’s try something different. So Professor Alexander built a cage that he called “Rat Park,” which is basically heaven for rats. They’ve got loads of cheese, they’ve got loads of colored balls, they’ve got loads of tunnels. Crucially, they’ve got loads of friends. They can have loads of sex.

And they’ve got both the water bottles, the normal water and the drugged water. But here’s the fascinating thing: In Rat Park, they don’t like the drug water. They almost never use it. None of them ever use it compulsively. None of them ever overdose. You go from almost 100 percent overdose when they’re isolated to zero percent overdose when they have happy and connected lives.

Hari isn’t saying that the environment is necessarily to blame, either, but rather that connecting with a drug addicted person is far more effective than punishing them, and maybe it is the cage. Hari questioned the relationship between these rats and their park, and thought, maybe it’s only with rats. But then he considers what happened with human beings, young American service men in the Vietnam War, over forty years ago.

“In Vietnam, 20 percent of all American troops were using loads of heroin, and if you look at the news reports from the time, they were really worried, because they thought, my God, we’re going to have hundreds of thousands of junkies on the streets of the United States when the war ends; it made total sense”. The Archive of General Psychiatry followed these soldiers home and conducted a detailed study, and what actually happened to these soldiers shocked scientists and doctors who studied addiction. Hari goes on, “It turns out they didn’t go to rehab. They didn’t go into withdrawal. Ninety-five percent of them just stopped. Now, if you believe the story about chemical hooks, that makes absolutely no sense, but Professor Alexander began to think there might be a different story about addiction. He said, what if addiction isn’t about your chemical hooks? What if addiction is about your cage? What if addiction is an adaptation to your environment?”

We’ve seen time and time again in countries with harsh drug policy and limited views of addiction, including the United States, shaming and criminalizing drug use—throwing addicts into the criminal justice system—does nothing positive for the addicted individual. When a heroin addict is arrested for possession and spends time in jail, she comes out with a record, thereby making it even more difficult for her to get a job and secure housing, further limiting her connections, isolating and traumatizing her, and creating a void that can seemingly only be filled with substance use. So what if, instead of beating people down, we built them up? What if we loved them unconditionally, and take all the money we spend on cutting addicts off, on disconnecting them, and spend it on reconnecting them with society? That’s what Portugal’s national drug coordinator, Dr. João Goulão, asked himself.

In the year 2000, Portugal had one of the worst drug problems in the world, with one percent of its population addicted to heroin—an incredibly mind-blowing statistic. They had tried the American way of waging war on drugs, which is essentially a war on drug addicts, and found that what we know to be true here was true for them: it does not work, and it was getting worse every year. Fifteen years ago, Dr. João Goulão and a panel of experts sat together to address the problem, and considered all the research, and the country of Portugal did something monumental, something daring and seemingly crazy: they decriminalized ALL drugs. With their drug problem reaching unmatched heights at that point, Portugal’s decision had the whole world watching.

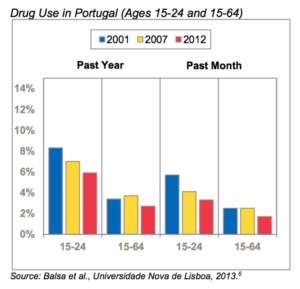

We know what happened, or didn’t happen rather: More people did not start using drugs. More people didn’t die from drug overdoses. What everyone thought was going to happen, didn’t happen. Drug use went down. WAY DOWN. Portugal went from having one of the worst heroin epidemics in the world in 2000 to being among the countries with the lowest prevalence of use for most substances in 2012. These were the results:

Fewer people arrested and incarcerated for drugs.

The number of people arrested and sent to criminal courts for drug offenses declined by more than 60 percent since decriminalization.

The percentage of people in Portugal’s prison system for drug law violations also decreased dramatically, from 44 percent in 1999 to 24 percent in 2013.

More people receiving drug treatment.

Between 1998 and 2011, the number of people in drug treatment increased by more than 60 percent (from approximately 23,600 to roughly 38,000). Treatment is voluntary – making Portugal’s high rates of uptake even more impressive.

Over 70 percent of those who seek treatment receive opioid-substitution therapy, the most effective treatment for opioid dependence

Reduced drug-induced deaths.

The number of deaths caused by drug overdose decreased from about 80 in 2001 to just 16 in 2012.

Reduced social costs of drug misuse.

A 2015 study found that, since the adoption of the new Portuguese national drugs strategy, which paved the way for decriminalization, the per capita social cost of drug misuse decreased by 18 percent

From DrugPolicy.org’s fact sheet.

In 2013, Nuno Capaz of the Lisbon Dissuasion Commission said, “We came to the conclusion that the criminal system was not best suited to deal with this situation… The best option should be referring them to treatment… We do not force or coerce anyone. If they are willing to go by themselves, it’s because they actually want to, so the success rate is really high… We can surely say that decriminalization does not increase drug usage, and that decriminalization does not mean legalizing… It’s still illegal to use drugs in Portugal — it’s just not considered a crime. It’s possible to deal with drug users outside the criminal system.”

So why is it so hard for people to accept the outcomes of these studies? For one, government campaigns have ingrained anti-drug slogans in our brains since elementary school, so these findings are contrary to our belief system, characterized by Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign. Since the war on drugs began with President Nixon in the 70s, immortalized by the first lady in 80s, and continued by the first President Bush, we have been engaged in a war against people affected by drug addiction. Four decades of throwing people struggling with addiction into prison, stripping people of their coping mechanisms, and offering them nothing in return except a criminal history. Secondly, if the drugs and the individual aren’t to blame, then who is? It is our responsibility as a society to help those suffering from addiction; to create a paradise for them, lend our unconditional support and sing them songs of love.

With no end to the war on drugs in sight, there are still things we can do to shift the tide and create a culture of love and support for the drug addicted person:

- Stop treating the addicted person as a criminal. More than half of us have been touched in some way by addiction, and many of us know someone who is struggling with addiction today. Shifting the way we look at and treat people with addiction is the first step. They are not criminals or deviants. They are not even addicts. They are human beings—our sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, neighbors, peers, colleagues and co-workers—who are coping with an illness.

- Support people in their addiction. Whether you’re a treatment provider, family member, employer or advocate, we all have a role in ensuring people who need treatment get the care they need and deserve. As we learn from Portugal, forcing people into treatment often results in high cost and poor outcomes. When someone is ready for treatment, is willing and engaged in their recovery, we see the greatest outcomes and people can begin their life free of substances.

- Connect with people. Showing someone struggling with addiction that you aren’t going to turn your back on them and that you care about their recovery is the most important thing you can do. Instinctively, we want to let our loved ones “hit rock bottom” or show them how their addiction has affected us by shutting them out, but we know this does not help. Just like the rats in “Rat Park”, your love might be the thing that makes this person say maybe I don’t want the drug-laced water.

The opposite of addiction is connection.

https://www.facebook.com/upliftconnect/videos/846444885492494/

If you or someone you know is struggling with addiction or a mental health issue, Roots Through Recovery is always open to help you. Visit us at 3939 Atlantic Ave, Suite 102 Long Beach, CA 90807 or call (866) 766-8776 for immediate assistance..

2 thoughts on “Portugal: a Case Study in Compassion”

I can’t thank you enough for this post!! I have been trying to explain this concept to people and get discouraged listening to them try to refute the idea with quotes, studies, etc. from doctors, therapists, police, scientists. I hope more professionals and addiction treatment services can come to this understanding. This is definitely a better approach. Thank you!!

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!